Edible Insects

Season 48 Episode 14 | 53m 28sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Take a tasty look at insect foods that could benefit our health and our warming planet.

From crunchy crickets to nutty fly grubs, NOVA takes a tasty look at insect foods and how they could benefit our health and our warming planet.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Additional funding is provided by the NOVA Science Trust with support from Mark and Nancy Jungemann. Funding for NOVA is provided by the David H. Koch Fund for Science, the...

Edible Insects

Season 48 Episode 14 | 53m 28sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

From crunchy crickets to nutty fly grubs, NOVA takes a tasty look at insect foods and how they could benefit our health and our warming planet.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The future of food is being revolutionized by science... ...as new research helps bring unexpected ingredients to the table.

Kind of tastes like shrimp.

They have this seafood quality to them.

It reminds you of, like, a Frito or a chip.

VALERIE STULL: Just, like, crunchy and a little oily and a little salty.

They taste like popcorn.

JESSICA WARE: A very smushy taste.

Like a pudding, almost.

JOSEPH YOON: The citrusy flavor, it's so incredible.

NARRATOR: Researchers are revealing these delicious ingredients could do wonders for our health.

TANYA LATTY: They're full of polyunsaturated fat, they're full of protein, and they have a whole range of trace minerals and micronutrients.

STULL: Potential prebiotic effects and potential reductions in gut inflammation.

Those two things are very exciting.

NARRATOR: So what are these miraculous foodstuffs?

Well, they're insects!

Thousands of edible species in all shapes and sizes.

It is gastronomy in the highest form.

Amen.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Not everyone is convinced.

What I would say to anyone that's nervous is, I'm right there with you still.

I'm right there with you still.

NARRATOR: But some researchers believe that chowing down on insects could have made our species smarter.

JULIE LESNIK: Our brains run on fat.

That extra fat in their diet contributed to supporting this little bit larger brain.

NARRATOR: And in the future, eating insects may help save us from ecological catastrophe.

To produce more meat than we already do is incredibly problematic.

STULL: The mass production and the way that we're doing it now is simply unsustainable.

LATTY: Insects offer so much promise.

They potentially could feed the world.

NARRATOR: But to make this change a reality, scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs must crack the secrets of insect farming.

Insect agriculture has the potential to radically transform the way we produce food around the world.

KEIRAN WHITAKER: It only takes nine to 12 days to turn what is a grain of sand into an inch-long protein bar.

Automation fits so nicely with this type of farming.

NARRATOR: But will all this be enough to persuade people to change their ways...

So that, I can see the bugs.

NARRATOR: ...and learn to love the bug?

MIKE RAUPP: On the count of three, we're going to go for it.

Ready?

One, two, three.

Cheers!

(whimpers) NARRATOR: Welcome to the wonderful world of "Edible Insects."

(crunches) NARRATOR: Right now on "NOVA."

♪ ♪ (birds chirping) NARRATOR: Our planet is teeming with life.

♪ ♪ But one of branch of the family tree is often overlooked: insects.

♪ ♪ I've always loved insects, as long as I can remember.

When I was a kid, I used to run around my neighborhood collecting insects and bringing them home to show my mom.

I think they're just amazing and fantastic animals.

NARRATOR: Entomologist Tanya Latty has been obsessed with insects for years.

And with good reason: insects are everywhere.

Two-thirds of known animal species are insects.

For every one of us, there are over a billion of them.

They've survived and thrived on Earth for nearly half a billion years.

And they've adapted to almost every possible ecological niche.

LATTY: Insects are the most diverse animals on the planet.

There are millions of species.

There are so many species that we're not even sure of the exact number.

NARRATOR: Either alone or in vast colonies, insects are a secret force that regulates our world.

They pollinate, clean up, and keep the rest of nature in balance.

They help make our world tick.

LATTY: We tend to overlook insects, and that's a great shame, because without them, our ecosystems wouldn't function.

I mean, they do everything.

How can you not love insects?

NARRATOR: But while some people love bugs, others just love the way they taste.

♪ ♪ To some, the idea of eating insects may seem strange.

But in places like Thailand, it's long been a cultural tradition.

♪ ♪ Very good, very good!

Delicious!

♪ ♪ (translated): I've got coconut beetle grubs, crickets, silkworm cocoons, grasshoppers, giant crickets, and bamboo caterpillars.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In Thailand, insect-eating originated in rural areas.

But over the last few decades, the culture has spread into the cities, where urbanites are developing a real taste for them.

♪ ♪ (translated): I usually eat them when I go out drinking with my friends.

They taste fantastic with beer.

(translated): I eat them as a snack between meals.

They are not scary at all.

They are extremely healthy and natural.

I highly recommend everyone gives them a try.

NARRATOR: Insect-eating isn't unique to Thailand.

Across the globe, over two billion people eat over 2,000 varieties of insect.

But not every bug makes a good meal.

So which species are the most popular?

At number five, it's the Hemiptera, including cicadas and water bugs.

By all accounts, they're quite a mouthful.

At number four, it's the Orthoptera, including locusts, grasshoppers, and crickets.

Hard to catch, but famed for their satisfying crunch.

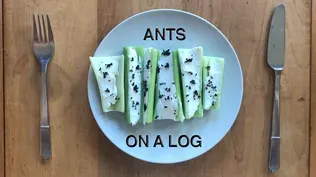

In at number three, it's the Hymenoptera: including ants, bees, and wasps.

The venomous ones can give their taste a citrus twist.

At number two, it's the Lepidoptera-- butterflies and moths in their caterpillar state.

In Southern Africa, millions of these fleshy favorites are devoured each year.

But at number one, it's the beetles-- the Coleoptera, especially their juicy larvae.

Together, these grubs and weevils make up nearly a third of all insect species consumed.

♪ ♪ Insects have been a part of the human diet for millennia.

But scientists are discovering they have a lot more to offer than just a taste sensation.

So, this is the larva of a scarab beetle.

So, when it gets older, it's going to look a little bit like a june bug.

NARRATOR: To understand why scientists are becoming so fascinated by insect-eating, this beetle larva is a good place to start, because its translucent skin allows you to see what's so special about an insect.

LATTY: If you look closely, you can see this white stuff.

That's an organ called the fat body.

It's not actually the same as fat.

It's more like a combination of fat and liver.

NARRATOR: Many insects have these spread throughout their bodies, one of several nourishing insect ingredients that are impressing scientists.

These are very nutritious.

They are full of polyunsaturated fat, they're full of protein, and they have a whole range of trace minerals and micronutrients.

NARRATOR: Compared to a steak, insects really stack up.

Steak is packed with valuable protein, iron, fats, and micronutrients.

But whether eaten as a fatty larva or in an adult form, pound for pound, many bugs equal or better the nutritional value of the finest steak.

And there could be even more nutritious species out there just waiting to be discovered.

We've only really started to investigate a tiny number, and given that huge diversity, there's a huge likelihood that they could have all sorts of different nutritional profiles-- some of which may be excellent for us.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Insects are clearly a great source of nourishment.

And this is leading some researchers to ask: Was an insect diet key to the evolution of the exceptional human brain?

♪ ♪ Biological anthropologist Julie Lesnik is studying a puzzling chapter in the story of human evolution: a remarkable increase in the brain size of our ancient ancestor Australopithecus.

Australopithecus was a small foraging ape that roamed the African savanna from just over four million years ago.

But something big is going on with her brain.

From about five million to up to two million years ago, we have this brain size expansion of about 20%.

NARRATOR: This is a substantial increase.

Its cause remains an evolutionary mystery.

But experts believe it probably took a special diet to support this larger brain.

Brains are energetically expensive.

And one thing they especially need are fatty acids.

Our brains run on fat, and fat is a very rare resource naturally in our environment.

So what were they eating?

NARRATOR: It's possible Australopithecus obtained this fat by scavenging the bodies of larger animals.

But Julie thinks there's an alternative and more surprising explanation.

Termite mounds pepper the African savanna, their rock-hard exterior protecting the fatty larvae within.

Our cousin the chimpanzee forages for termites today using ingenuity and simple tools to penetrate the termite fortress.

LESNIK: Chimpanzees can thread into that termite nest with a flexible probe made of either grass or a green branch, and the soldier caste bite on to the end of that tool, and then chimpanzees extract them from the mound and eat those termites right off that probe.

NARRATOR: This technique harvests the adult insects.

But to get the fatty larvae, you must penetrate further into the mound.

Intriguingly, a number of almost two-million-year-old animal bones have been unearthed in South Africa.

Their smooth, rounded ends show clear parallel scratches.

Scientists believe these are wear marks from repeated strikes, and that the bones are actually Australopithecine tools used for one specific job.

This is a prototype, basically, of the types of tools they were using two million years ago.

A tool like this can get through, especially if you have a fragment that has kind of a pointier end that lets you penetrate it.

We can pretty confidently say that these bone tools were used to dig into termite mounds.

(pounding) NARRATOR: Breaking open the mounds could have given Australopithecines access to the nutritious fat of the termite larvae: instant brain food.

By just adjusting a little bit how they utilize the same resource, it's probably enough to get them that extra fat in their diet that contributed to supporting this little bit larger brain.

(insects buzzing) NARRATOR: Insects may well have provided our ancestors with key nutrients at a crucial point in their development.

♪ ♪ But our bodies' relationship with insects may not have ended in the distant past.

There's growing evidence that an insect diet may influence more than just our brains.

Recent research suggests that a key process in our bodies gains significant benefits from eating insects.

Our digestion.

Health scientist Valerie Stull is fascinated by the microorganisms that populate our digestive system.

STULL: Gut bacteria are incredibly important to human health.

We actually have more bacterial cells in our bodies than we do human cells, and they play a huge role in our overall health and well-being.

NARRATOR: But some strains of gut bacteria are unwelcome guests.

Too many of them make our gut prone to inflammation and disease-- even cancer.

There's mounting evidence that some modern Western diets are upsetting the healthy balance.

STULL: Diets that are very, very high in red and processed meats can lead to imbalances in gut microbiota.

We know that refined sugars, refined grains are also not particularly good for promoting that healthy ecosystem within the gut.

NARRATOR: Valerie wondered whether the insect diet enjoyed in many parts of the world could improve gut health.

I wanted to investigate, what are the potential health impacts of eating insects beyond just their nutritional composition?

NARRATOR: Valerie gave 20 volunteers a milkshake to drink once a day for two weeks as a part of their regular diet.

The milkshakes of half the group had insects ground and blended into them.

When their gut bacteria was checked, Valerie discovered the insect shake was having a noticeable effect.

STULL: We saw potential prebiotic effects in terms of promoting the growth of healthy bacteria and potential reductions in gut inflammation.

Those two things are very exciting.

NARRATOR: What could cause these changes?

The answer may not lie with what's inside an insect, but what's outside it.

Unlike vertebrates, insects do not rely on an internal skeleton.

Insects don't have bones inside their body.

Instead, they have the support on the outside.

It's a little bit like a suit of armor, and we call that an exoskeleton.

NARRATOR: It's the material the exoskeleton is formed from that makes it so special.

The exoskeleton's made out of chitin, which is this stiff, fibrous material that gives it the structure.

NARRATOR: It's unclear if humans can digest chitin fiber.

But when ingested, it appears to stimulate the growth of good gut bacteria in a way that other dietary fiber may not.

Chitin may be a missing ingredient that helps generate a healthy, balanced digestive system.

This can relate to so many human health conditions.

We need more variable gut bacteria.

We need abundant populations of these healthy bacteria.

It suggests that in our past, chitin from insects was probably part of the natural, normal, basic human diet that was used to keep a healthy gut.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: So, in the past, insects in our diet may have made our species not just smarter, but healthier, too.

And today, they continue to serve as an exceptionally nutritious food source.

But some experts claim that eating bugs could do even more, and help solve a looming global crisis.

Forecasts predict that by 2050, the human population will have swelled to over nine billion.

If current eating habits continue, that would mean a doubling of meat production.

But that could prove very damaging to our planet.

How we produce meat is awful for the environment.

So to produce more meat than we already do is incredibly problematic.

NARRATOR: To produce a pound of beef compared to a pound of corn takes seven times more water and 100 times more land.

This contributes to droughts and high levels of deforestation.

Many scientists and policy makers are now suggesting that if we hope to feed everyone, we need a fundamental change.

STULL: It's not to say that conventional animal agriculture can't fit in with a sustainable food system, but the mass production and the way that we're doing it now is simply unsustainable.

NARRATOR: The answer may lie in exploiting a special ability found in many invertebrates.

It turns out that insects have the potential to make protein far more efficiently than other animals.

The reason lies in their physiology.

LATTY: Animals like mammals and birds are warm-blooded.

So what that means is that we generate a tremendous amount of body heat.

Insects are a little different.

This is a thermal camera, and what it'll let us do is detect heat.

NARRATOR: On the image, Tanya's skin appears red, meaning it's warm.

As a mammal, she is endothermic, burning food to generate internal heat.

But the spiny leaf insect appears blue, meaning it's cool.

It is ectothermic.

Ectothermic refers to the fact that some organisms are unable to generate body heat.

If it's warm outside, their bodies are that same temperature.

If it's cold, they're also cold.

NARRATOR: This physiological difference has a major effect on the quantity of resources they need to grow.

Since insects aren't wasting energy trying to keep their bodies warm, most of the calories they eat can be converted into nutrients that we could then eat.

So you get a much higher conversion efficiency with an insect than you would with a mammal.

NARRATOR: When it comes to generating animal protein efficiently, insects rule.

To produce a pound of beef requires nearly ten pounds of feed.

But growing a pound of insects needs less than two pounds.

One pound of beef also requires over 2,000 gallons of water.

But the same weight of insect can take less than 12 gallons.

LATTY: If you're farming an insect, you don't need to feed them nearly as much as you would a mammal of the same size.

Insects offer so much promise.

They are a really accessible form of protein that, you know, potentially could feed the world.

NARRATOR: The numbers look great.

But can humanity really move from farming pigs, chickens, and cows to farming insects?

If we are going to feed billions, the amount of insect protein needed will be enormous.

Over 90% of insects consumed today are foraged from the wild.

The palm weevil-- probably the most popular edible insect of all-- is harvested from rotting palm trunks.

But natural harvesting like this could not be scaled to feed billions.

STULL: It's local and it's free.

But really, the way to utilize insects better as a food is to help people farm them and engage in insect agriculture.

NARRATOR: Change is already happening.

In Thailand, the last few decades have seen a surge in start-up insect farms, led by entrepreneurs like Thanaporn "Kaew" Sae Leaw.

(translated): We heard about insect farming from our relatives.

They said it's something you can do as a sideline, without giving up your day job.

In this container, I've got a batch that are already 15 days old.

Here, let me show you.

NARRATOR: In Thailand, crickets have become these new farmers' insect of choice.

Because not only does cricket farming take up very little space, but their rapid growth allows farmers to continually harvest year-round.

But there is still a lot to learn.

The field of insect agriculture is really in its infancy.

So learning to farm insects at scale to feed lots of people, we're just now scratching the surface.

NARRATOR: Farming insects definitely comes with unfamiliar new challenges.

Much of Thanaporn's time is spent keeping her ectothermic charges at the correct temperature.

SAE LEAW (translated): We've always got to keep a close eye on the weather.

Sometimes when it gets too hot, we have to spray water on the crickets to cool them down.

NARRATOR: And cattle farmers don't have to deal with the problem of cannibalism.

(translated): Unfortunately, if there's not enough food, they do start to eat each other.

That's one of the reasons we have put in these egg cartons-- it gives the vulnerable ones somewhere to hide from their voracious companions.

NARRATOR: But it's worth the effort.

With low costs, low maintenance, and a quick turnover, Thai farmers are taking to the emerging industry in the tens of thousands.

(translated): Most of the time, there aren't enough for us to eat.

We have all sold out.

And if the demand gets any higher, we might have to expand the farm.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: With healthy domestic demand for these tasty snacks, Thailand's insect farms look set to grow.

But what about the U.S.?

How close is America to being conquered by the insect-eating bug?

(buzzing) Baltimore, Maryland.

Entomologist Mike Raupp leads his Cicada Crew on an insect hunt.

RAUPP: So you can see this ancient pin oak tree.

This one's probably been here maybe for 100 years.

NARRATOR: Among the roots of the tree, the soil seems alive.

Periodical cicadas are returning to the surface, the advance guard of "Brood X."

These insects have spent nearly two decades alone below ground.

But after 17 years, it's time to breed.

RAUPP: They come out at dusk, they climb the tree, they try to escape their shells, then get up to the relative safety of the treetop.

NARRATOR: Where they mate in their multitudes.

This happens nowhere else on Earth except right here in the Eastern United States.

And this is the big brood.

DEMIAN NUNEZ: This is what I was hoping for.

I'm just really impressed by the density that's in this neighborhood.

NARRATOR: Brood X is so famous because the numbers are phenomenal.

There can be up to 1.5 million of them an acre, coating every available surface.

Overloading the environment is actually their survival strategy.

Synchronizing a rare 17-year emergence allows them to outlive some predators and overwhelm the rest.

(buzzing) It guarantees their bizarre strategy of predator satiation.

Filling the belly of every predator that wants to eat them and still having enough left over to perpetuate their species.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Not so long ago, it wasn't just birds and other small animals that benefited.

These emerging broods were once a nutritious windfall for Indigenous communities.

LESNIK: When we think about, "Are insects consumed here in North America?"

They were a traditional part of many diets of many different tribes.

We've lost a lot of this history, partially because of the removal of these populations from their native lands.

RAUPP: I know that Indigenous people ate cicadas.

It was a bounty for them.

So from my interest as an entomologist, I certainly am going to snack on just a few periodical cicadas.

NARRATOR: For a dedicated entomologist, eating a cicada is a rite of passage.

We're just going to, on the count of three, we're going to go for it.

You guys ready?

Who's up?

(woman speaking indistinctly) We're all up?

Jessica, are you up?

I'm up.

All right, thumbs up.

Ready?

One, two, three.

Cheers!

(whimpers) Pretty sweet.

RAUPP: What's the flavor?

What do you get?

Demian?

Slight nuttiness.

It does taste like nut a lot-- I wasn't expecting that.

Oh, my God!

NARRATOR: Mike encourages his grad students to experiment with this insect bounty.

SAENZ: The idea is to, like, spread the wings a little bit, so they can, I don't know, like, like, get crispy, and then you're just eating the abdomens over here.

That's what I'm thinking.

RAUPP: People eat raw oysters, they eat raw clams-- creatures that live at the bottom of a bay and filter you-know-what out of the water.

Now, why wouldn't somebody eat a periodical cicada that's been sipping plant sap for 17 years?

NARRATOR: The roots of some Americans' resistance to insect-eating aren't hard to find.

This country's culinary attitudes largely originate from the prejudices of Northern Europeans.

America was settled by European colonists, and the bulk of insect diversity is really around the Equator.

It's not in England.

(laughs) LESNIK: So, insects weren't largely available.

The diets in these northern latitudes tend to be very meat-centric, because that's what's available to get you through harsh winters.

WARE: Early colonists noted that Native people in parts of the United States consumed insects.

But that was considered to be an "other," I think.

That was something that a different group of people ate.

And so I don't think it was widely adopted.

Really good.

Yum!

NARRATOR: Hundreds of years later, some think it's time to move past this culinary bias.

(laughs softly) NARRATOR: If the global food industry is going to reinvent itself, many believe the change must start here, because wealthy countries like the U.S. play a leading role in setting global attitudes.

It's simply true that our dietary preferences are driving marketplaces for food trade across the globe.

So I think if we can do nothing else, if we can change the perception of insects as food in the West, that would be a positive step forward.

NARRATOR: But that could be a challenge.

Many Americans aren't just neutral towards bugs, they're horrified by them.

(screaming) NARRATOR: In cultures without a history of eating them, insects are often associated with decay and disease.

WARE: People often associate flies, for example, with things that are unclean, or cockroaches with things that are unclean.

And so nobody really is going to think, "Oh, I... That's going to be a good food item," if you see something crawling out of your, your sewer drain.

Having disgust as your first impression for something you're about to eat, that's a pretty bad first impression.

NARRATOR: This disgust response might look like an instinctive reaction to potential threat.

People generally can recognize the disgust face very easily.

In one, the lower jaw drops and the tongue is extended.

And another version, it's just raising the upper lip, closing the nose a little.

But it's associated with the feeling of nausea.

And that, again, reminds us that disgust is originally about food, because nausea is a food rejection sensation that gets us to stop eating.

NARRATOR: But in reality, compared to other livestock like cows and pigs, edible insects are unlikely to carry pathogens that are harmful to humans because insect physiology is so different from our own.

Psychologists are now finding that disgust towards insects is nothing more than a socially acquired response.

WARE: Children are not born with an innate distaste for insects.

You know, in fact, many young toddlers would grab an insect, and the first thing they would do is put it towards their mouth.

There's no innate disgust.

It's almost entirely, I would say, social conditioning.

Getting people to like insects is part of a general problem of getting people to like anything.

NARRATOR: So, if disgust is more nurture than nature, is it possible to get mainstream America to love the bug?

New York chef Joseph Yoon is a passionate advocate for edible insects.

YOON: I'm not saying that we can save the world by eating insects, but the idea that we can make small lifestyle choices that can positively impact the environment and future generations, that's of great inspiration and motivation to me.

NARRATOR: Joseph has agreed to run an experiment for "NOVA."

He's constructing a tasting menu designed to see if some New Yorkers could be converted to insect eating with a little creative cooking.

YOON: People tend to think in extremes when it comes to edible insects.

They think of insects, something that's gross, and something that they don't want to eat.

We need to redefine the idea of edible insects from the ground up.

And it's a matter of shifting perceptions from insects being gross to show that they're delicious!

Here are some roasted crickets.

These are black ants that have the formic acid as a defense mechanism, which gives it a citrusy flavor.

It's so incredible.

These are mealworms that we have here.

These have a nutty, earthy, umami flavor.

These are chipotle-flavored grasshoppers.

These are wonderful, just, snacks.

NARRATOR: With ingredients like these, Joseph's task is hard, but not impossible.

♪ ♪ Because America's socially conditioned disgust has been successfully reversed before.

Just consider your nearest sushi counter.

50 years ago, sushi restaurants were rare in the U.S.

Many Americans were squeamish about eating uncooked fish.

STULL: It was disgusting-- raw fish was disgusting.

Then it, you know, permeated the coasts.

You got it at a fancy restaurant in New York or San Francisco.

Now you can get sushi at a gas station in Nebraska.

Food culture does change.

NARRATOR: Some experts believe that sushi's breakthrough in the U.S. was thanks to the creation of the California roll, where the unfamiliar ingredients are hidden by a rice exterior.

It's all about clever psychology.

So could Joseph leverage this same trick for insects?

While he prepares his menu, the tasters arrive.

I'm pretty adventurous, yeah, it's exciting, it's fun, yeah.

I'm nervous, but also very excited.

I would consider myself a pretty adventurous eater-- at least a nine out of ten.

I'm actually kind of excited!

Always willing to try something new, and, you know, push the boundaries.

♪ I like bugs with 16 legs and bugs with lots of eyes ♪ ♪ I like spiders that crawl on the floor ♪ ♪ And eat up all the flies ♪ A great strategy for trying to convince people to try edible insects is to incorporate it into food they already know and love.

To start off, we have a blueberry hopper muffin with grasshoppers.

♪ I love bugs that live in the mud ♪ We have azcayo guacamole with black ants, crickets, citrus, chili peppers, onions, and garlic.

♪ I like bugs ♪ And then we have pizza cavalletta, with a locust bolognese, mozzarella, pecorino romano, and basil.

Bug appétit!

(chuckling): All right, here we go.

NARRATOR: So what will the tasters think?

CHENG: Ooh... (laughs) There's a really big one in there.

♪ ♪ (chuckling) Nice little crunch factor.

(laughs) You definitely know it's... (laughs) ...not a fruit.

This one I'm nervous about.

(laughs) Yeah, so that, I can see the bugs.

GOLDBERG: I'm trying to get, like, the least intimidating bite.

(laughing, crunching loudly) So scary!

(laughs) These really look like little bugs, so... Um, so that part was a little rough.

It doesn't weird me out, because I know that it's prepared to be eaten, edible.

But if I went probably to a place by my house and got guacamole and found crickets in it, I'd have an issue.

Pizza!

Okay.

This one's a little iffy, but I'm going to try it anyway.

I'm going to go for the big bug right there.

I think this is a locust right here.

Okay.

(exhales) ♪ ♪ I think the, the pizza masks the, the taste of the bugs, so...

I didn't actually taste much of the locust, which is good.

I don't know if I would order something, seeing something, a big bug right there.

Maybe if it was not seen as much?

If I think about what I ate, it's...

Challenging.

(laughs) NARRATOR: Despite Joseph's skills, the main courses have produced a mixed reaction.

So, for dessert, the chef goes one step further.

YOON: A delicious banana bread with a vanilla buttercream frosting.

Surprise!

There's mealworm powder in both the banana bread and the frosting.

The psychological advantage of using insect powder is that you don't have to see it.

(laughing): Amazing!

NARRATOR: Joseph may have struck pay dirt with the powdered insects.

Mm!

That's delicious.

I feel like this one I'm actually the least intimidated by, because it is, um...

It's powder, so it's-- you don't see a physical bug.

You can't taste anything different than a normal banana bread.

(chuckling): I actually really like that, that's awesome.

That's really delicious.

NARRATOR: Perhaps insect powder is the secret weapon to overcome America's disgust.

Insect powder is so versatile.

You can add it to your smoothies, you can add it to soups, you can add it to sauces.

You can add to your mac and cheese sauce.

You can add it to your fried rice.

You can add insect powder to virtually any type of food.

Because of Americans' attitude towards insects, I think it's going to be a really successful way to introduce them to insect protein.

(laughing): I would probably finish this.

NARRATOR: But there's a problem.

Pound for pound, insect protein producers cannot currently get close to the prices charged by their established livestock rivals.

If prices stay as high as they are, consumers are unlikely to make the switch.

But could science and technology help close the gap?

♪ ♪ Canadian Mohammed Ashour is an insect farmer with big plans.

ASHOUR: We are building the world's densest, smartest, and largest commercial cricket production and processing facility.

Insect agriculture has the potential to radically transform the way we produce food around the world.

NARRATOR: Mohammed runs a start-up company that hopes to bring down the costs of insect farming.

Their plan is based on research from their R&D facility in Austin, Texas, aimed at cracking the code of farming the cricket.

♪ ♪ Chief operating officer Gabe Mott manages the cricket research project.

MOTT: The high expense of insect protein generally is predominantly because it's a novel industry.

We need to understand the organisms as, as well as we possibly can, provide them exactly what they need to thrive, and then eventually, begin selective breeding.

NARRATOR: Cows, chickens, and pigs have been selectively bred as food for millennia.

In contrast, edible insects remain much closer to their wild origins.

MOTT: The process of selective breeding crickets has really only just begun, and there's a, a long way for us to go.

The good news is, we obviously can deal with much larger herds, crickets lay vastly more eggs, their life cycle is shorter, and we can take advantage of modern, cutting-edge technology.

We get to apply that from day one, as opposed to centuries into the breeding process.

NARRATOR: But breeding alone is not enough.

They're trying to figure out the perfect environment to make the crickets thrive.

They use ten different growing rooms to allow side-by-side comparisons for different feed, temperature, and lighting levels.

Hundreds of sensors keep the environment under surveillance.

MOTT: We observe the consequences of manipulations and changes on the insect biology, on their physiology, on their health and well-being, and then adapt and build on that and adapt and build on that.

NARRATOR: Aspire claims that due to five years of in-house research and proprietary technology they've created, they've greatly increased production efficiency and yield.

MOTT: We saw these, these massive gains.

We were able to shave weeks off the life cycle time, drastically improve survivability, and develop an understanding of the optimal density for cricket colonies.

We now harvest ten times the amount of crickets from the exact same bin that we did five years ago.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Even if that's true, to compete commercially with industrial livestock producers, insect farming would need to scale up dramatically.

And this is where insects come with a built-in advantage.

You can't put cattle into a giant racking system.

They're not going to be happy.

Whereas insects are really almost custom-made perfectly for automation solutions that exist already.

A robot can just wander around whenever the time is appropriate and deliver all the feed.

I know to the gram how much feed is being fed, and I know, effectively to the second, when that feed is being delivered.

NARRATOR: They believe the combination of higher yields and intensive automation may soon allow insect farming to compete directly with traditional livestock rivals.

ASHOUR: Over the course of the next decade, insect protein will go from being a really interesting novel ingredient to being a mainstream protein alternative.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Mohammed and Gabe are not the only ones who see the potential.

Across the world, many companies are figuring out how to farm insects commercially.

If costs continue to drop, cheap, nutritious insect protein may soon revolutionize the global food supply system.

♪ ♪ One of the many researchers hoping to contribute to this burgeoning industry is entomologist Ebony Jenkins, a doctoral student at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore.

JENKINS: With the market booming, I believe that there are going to be many opportunities.

This is going to open the doors for a lot of people, and we're going to be seeing insect-based products soon on our local shelves.

NARRATOR: But Ebony did not grow up loving bugs.

JENKINS: Five years ago, I was deathly afraid of insects.

So I went from running from them, to chasing them, to eating them.

Now, that's revenge.

(laughs) NARRATOR: Her focus is on improving insects as a source of nutrition by modifying what they are fed.

JENKINS: One of my objectives is to understand the optimization of feed for various insects.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Every bug has a different preference.

Mealworms like dried foods, whereas crickets like vegetables and even animal protein.

But whether they are herbivorous, carnivorous, or omnivorous, many insects can be highly selective in what they eat.

They will choose foods to naturally regulate the nutrients they take in.

The trick for researchers like Ebony is to create a diet that insects will not only choose to eat, but which loads them with bonus nutrients.

You are what you eat.

So whatever they eat, they're able to metabolize, and we can benefit from those items that are present in their system.

So, for example, if you add more calcium or something like that to their diet, they're able to ingest that and pass that on.

There's a lot more tinkering that we could do to make sure that these diets don't just rear a bunch of insects, but they actually rear insects that have high nutritional value.

I think that just as pasta is, just as bread for your sandwich is, it's a great vehicle to pass on specific nutrients that we know are needed for, for healthy development.

NARRATOR: But beyond nutrients, Ebony wants to investigate the potential of insect food to deliver medicines.

Her focus is on CBD from cannabis.

JENKINS: We are analyzing the crickets to see how they metabolize CBD for medicinal purposes.

We just added those drops to the feed and mix it up, and we're just going to let them eat it, and see what is the CBD doing inside of the cricket.

WARE: I think it would be useful to try and incorporate medicinal products into insects, but it would be interesting to see if it actually would work.

Insects certainly can retain a lot of things in their tissue.

It would be interesting to see whether insects would metabolize them and, and chuck them, or whether they would actually be sequestered in the body tissue.

I'm not sure.

NARRATOR: Research is in its early days, but Ebony's confidence is high.

JENKINS: Once we have the findings, I believe that it's going to take off, because people want to know how they can become healthier.

And if we can make people's lives better, we did our job.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: If Ebony is successful, insects bred on the customized food could one day treat both your hunger and your health.

While some insects have discriminating tastes, others will eat just about anything.

And that could help tackle another major problem: food waste.

♪ ♪ Each year, 1.8 billion tons of food, worth approximately $1.2 trillion, is left to rot.

But for some, this toxic food dump is a golden opportunity.

The term "waste" is, um, a myth.

This is just a really good resource that we have yet to learn how to utilize.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In the heart of London, England, environmentalist Keiran Olivares Whitaker has a plan to turn rotting food waste into an economic and environmental gold mine.

♪ ♪ He's set up a company that is putting insects on the front line of the ecological battle.

Like Mohammed and Gabe, Keiran's initial focus is on research.

But unlike them, he's not breeding crickets.

This is the black soldier fly.

It could be the ultimate ecowarrior.

These bugs don't sting, don't damage crops, and don't carry disease.

And their larvae have really caught the eye of prospective insect farmers because there's something very special about their stomachs.

They are the least fussy eaters.

They will eat almost anything.

Because they are a fly species, the larva eats the decaying matter, so the things that are already rotting or composting.

So, we're not restricted to having to feed them on, you know, fruit and vegetables, or wheat.

We can use any type of food waste to feed black soldier flies.

NARRATOR: Researchers have discovered that the gut of the black soldier fly larva is filled with powerful enzymes.

These are super-efficient at digesting rotting organic waste.

I think there's huge potential to use insects as waste recyclers.

It's kind of one of their underexplored superpowers.

WARE: Some insects really do prefer decaying matter.

They really do prefer organic waste.

Why not harness the power of these voracious insects?

NARRATOR: Keiran's company, Entocycle, is already experimenting with a wide variety of different food waste.

WHITAKER: In this local area, we're using brewery grain waste, coffee waste, fruit and vegetable waste from the markets.

And, you know, these are all fantastic inputs to feed black soldier fly.

NARRATOR: And once they've digested the waste, black soldier fly larvae become the ultimate natural fast food.

WHITAKER: They grow incredibly fast, nearly 5,000 times their body weight.

So it only takes nine to 12 days to turn what is a grain of sand into an inch-long protein bar.

And that's why they're so fantastic.

From an environmental point of view, the speed of production for black soldier fly and the fact that they can eat the widest range of input streams mean that for me, they're just simply the best insect that we can farm.

NARRATOR: The company plans to concentrate initially on powder for pet and animal feed.

But in some parts of the world, black soldier fly protein may soon be on the dinner table.

WHITAKER: It's coming quicker than people think.

The legislation for black soldier flies for humans in Europe is changing as we speak.

I think you'll start seeing black soldier fly-based products entering the market kind of in 2021 onwards.

WARE: On a scientific level, I think it's terrific.

I think it makes a lot of sense.

I think it's probably economical and it's probably better for the planet in the long run.

I do feel a little bit squeamish about it, but I'd be game to try it.

If they were cooked well.

(laughs) ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Many experts now believe that the age of the insect meal is upon us.

♪ ♪ The unconstrained expansion of livestock farming still threatens widespread ecological devastation.

But scientific and technological progress in the field of insect farming mean edible bugs might provide a way out.

There are still problems to solve and attitudes to overcome.

But ready or not, insects could soon be back on a lot more menus.

LESNIK: I don't recommend that we're going to stop eating meat altogether, and everybody's all of a sudden going to eat insects.

Instead, what we're trying to do is expand our diets.

STULL: My hope is that anyone who would be watching this would at least take a moment to think differently about insects as food.

Because they are a totally awesome, underexplored food resource that has a ton of potential to improve the world.

Oh, I love the idea of eating insects.

I think it's a really good step in the right direction.

Insects are really sustainable and they taste great.

I mean, there's such a huge variety of insects that we're going to be able to find some that we like.

YOON: People often ask, like, "What's the best bug or best dish to get people to try it?"

There's no silver bullet.

I think diversity is going to be key.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: So what would the experts suggest?

♪ ♪ WHITAKER: Black soldier fly larvae.

They taste like macadamia nuts.

A little bit nutty, a little bit oily-- really quite nice.

♪ ♪ Grasshoppers kind of taste like shrimp.

They have this seafood quality to them.

JENKINS: The cricket has, like, a mild flavor.

It's not really overbearing.

It kind of reminds you of, like, a Frito or a chip, of something of that nature.

I think the best way I've ever had them was mealworms in garlic butter sauce-- those were tasty.

WARE: It would be a dragonfly, for sure, because their, their thorax is just muscle.

Get rid of the wings and get rid of the abdomen, and then go right for the thorax.

It's meaty and it's, it's really delicious.

What I would say to anyone that's nervous is, I'm right there with you still.

I'm right there with you still.

STULL: My favorite are the flying ants.

They taste like popcorn.

I mean, they're just, like, crunchy and a little oily and a little salty, and, like, they're really delicious.

YOON: There is one all-time favorite, hands down, no question, and that is the cicada.

They have a little exoskeleton and then they're full of this meaty flesh.

Amazing.

This is kismet.

This is romance.

This is poetry.

It's music.

And it is gastronomy in the highest form.

Amen.

JENKINS: My least favorite insect that I have tried is the sago worm.

I don't even want to talk about it.

(laughs) ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ALOK PATEL: Discover the science behind the news with the "NOVA Now" podcast.

Listen at pbs.org/novanowpodcast or wherever you find your favorite podcasts.

ANNOUNCER: To order this program on DVD, visit ShopPBS or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

Episodes of "NOVA" are available with Passport.

"NOVA" is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S48 Ep14 | 29s | Take a tasty look at insect foods that could benefit our health and our warming planet. (29s)

Insects Make Protein More Efficiently Than Mammals

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S48 Ep14 | 5m 14s | Most of the calories insects eat can be converted into nutrients that we can then eat. (5m 14s)

Was Eating Insects Key to Human Brain Evolution?

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S48 Ep14 | 3m 32s | Insects may have provided humans' ancestors with key nutrients. (3m 32s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Additional funding is provided by the NOVA Science Trust with support from Mark and Nancy Jungemann. Funding for NOVA is provided by the David H. Koch Fund for Science, the...