Here and Now

In Focus with Susan Kerns: Celebrating Cinema in Milwaukee

Clip: Season 2300 Episode 2337 | 52m 40sVideo has Closed Captions

Murv Seymour talks with Susan Kerns about creating cinema and filmmaking in Wisconsin.

Murv Seymour talks with Milwaukee Film Festival Director Susan Kerns at the Oriental Theatre about creating cinema, the magic of watching movies in person, and filmmaking opportunities in Wisconsin.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Here and Now is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin

Here and Now

In Focus with Susan Kerns: Celebrating Cinema in Milwaukee

Clip: Season 2300 Episode 2337 | 52m 40sVideo has Closed Captions

Murv Seymour talks with Milwaukee Film Festival Director Susan Kerns at the Oriental Theatre about creating cinema, the magic of watching movies in person, and filmmaking opportunities in Wisconsin.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Here and Now

Here and Now is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[percussive music] - Murv Seymour: Susan Kerns, welcome to "In Focus."

- Thanks so much for having me.

- I really appreciate you making this incredible space here at the Oriental Theatre available for us to sit and have this chat.

What kind of vibes do you get when you walk into this place?

- I mean, honestly, every time I walk in here, I just feel lucky that I get to keep walking in here.

This space is obviously gorgeous.

And so many cities didn't preserve spaces like this.

So it's such a treasure that we still have this.

- Yeah, this building is what, like, 98 years old or something like that?

- Yeah, I think we're approaching our 100th anniversary.

- Yeah.

- Mm-hmm.

- What about the folks that aren't Wisconsinites in the Milwaukee area?

Give them a little brief history of this space here.

- So the Oriental Theatre is really the only theater that is decorated or adorned in the style that it is.

If you go into the main house, we have six different giant gold Buddhas, and then we obviously have elephants, lions, all kinds of animals, peacocks in the main house.

And so what it is, is it's sort of capturing this sort of South Asian vibe.

And again, you know, of a very specific era.

Probably if we were doing this today, it would be done differently.

But it has, just, it's meant to really transport people to another part of the world, to a totally different kind of experience when you walk through those doors.

And then walking into the main house, again, it sort of exposes you to the glory of the space, transporting you.

- It's crazy to think that it's been sitting here since, like, 1929 or something like that.

That's crazy.

- Yeah.

Well, and the people that have gone through here.

Obviously we have movies, right?

But the Violent Femmes famously got their start here opening for the Pretenders.

We have had all kinds of musicians play this stage, like R.E.M., Iggy Pop and the Stooges.

Blondie played here.

I believe Patti Smith played here.

So all of these legends have come through.

I heard Bruce Springsteen played here.

Just amazing, rich history in this space.

- Yeah, that's pretty cool.

- Yeah.

- So, now, you're executive director of the Milwaukee Film Festival.

- Yep.

- Give me a little sense about your journey into filmmaking.

What makes you, how did you become so passionate about films?

- [laughs] Well, I grew up in Iowa, and-- - That'll do it.

- [laughs] I mean, kind of.

At the time, it did.

My parents loved movies, and it was sort of a family tradition for us to go to the movies a lot.

I have probably my earliest memories of my family, we would go to the mall 'cause the cinema was attached to the mall.

We would play pinball before we went to a movie, and then we'd go see a movie.

And I have memories of seeing films that I look at the dates now, I was, like, four years old going to the cinema, watching films.

I have a very specific memory of seeing one of Peter Sellers' "Peter Pa-," or "Pink Panther" films.

And the opening starts with the Pink Panther, and then it turned to Peter Sellers, and I was so disappointed.

I was just like, "Oh, I just wanted the cartoon."

- I was gonna say, now, is that your first memory of going to a film?

Like, that was your first film you ever went to?

- It's probably my first strongest memory, but I know that I saw other movies in the theater when I was very young, so I'm not sure.

They all kind of jumble together.

- You won't believe what my first one was, and it was at a drive-in theater.

- Okay.

- I'll give you the year.

Roughly '72, '71.

- Okay.

- And it scared the daylights out of me.

- Oh, um... - Wild guess?

- I was gonna say "The Exorcist," but I think that was '73.

- That was a little later.

- Okay.

- "Planet of the Apes."

- Oh, yeah!

- That movie terrified me.

- I bet.

[both laugh] - But I enjoyed it.

I remember going to see it.

I was, pretty sure I was in Detroit at the time, and it was like a double feature.

And I think it was, like, the movie, I think it was "Super Fly."

- Yeah.

- And then "Planet of the Apes..." - "Planet of the Apes."

- ...came on afterwards.

But, yeah.

- Yeah.

I mean, drive-ins in those days, like, just such a great experience.

And you never knew what you were going to see, 'cause the first film was, like, "This is what we're here to see, and then here's the second one."

- Now, and we've got some younger folks out there that might be listening or watching this, and they're thinking, "Drive-in, what's a drive-in?"

Please explain.

- Well, it's, I mean, you literally drive in, you sit your car in front of a giant outdoor screen.

You know, if you're being good, you go buy your popcorn from the little center area.

I remember us bringing in, like, brown grocery bags full of popcorn.

I don't know if your family did that.

[laughs] - Oh, yeah.

Cheaper than buying the food at the concession stands.

- Exactly, yeah.

- And it was a family thing.

Like everybody, like, I remember being in a big old wagon with my cousins, and we'd be sitting in that little back portion of the wagon with the glass and... - Yeah.

- You know, not watching the film, just poking fun at each other and that sort of thing.

- Yeah.

- But it was a big deal.

- It was so much fun.

- Whether you did the...

I kind of feel like a drive-in was a bigger deal than going to the actual, like a movie theater, though.

I don't know how that was for you.

- Yeah, it felt, again, sort of like an event.

You know, and all of the kind of texture of the experience, like you'd look over and somebody would be, like, opening their trunk and a couple kids would be popping out, you know?

And, yeah, just the-- there was always a playground.

- No, you can get lost during the middle of the movie and nobody'd know where you are, and you come back, long as you got back by the time the end of the movie was over, you're good to go.

- Yeah, right.

- Yeah.

So then going to the movies as a kid, you know, watching Peter Sellers, did that do something to you?

Did that make you say, "Hey, I might be interested in doing this," in terms of filmmaking?

- Well, I'll tell you, when I got a little bit older, I started to see foreign movies, and I have a very distinct memory of seeing-- I was traveling with my friend Kim, and we went to Colorado and saw the movie "My Life as a Dog."

This is a Lasse Hallström film, and it was a coming-of-age movie, you know, from a different part of the world.

And so I feel like that moment kind of blew open my understanding of the world.

I'd never really thought about kids in Europe before, and how I could so relate to people in a geographic area that I just didn't know.

I've always been very curious.

My parents have always, you know, we traveled a lot, road trips in the U.S., but we didn't ever travel overseas when I was a kid.

So having that experience then made me want to learn more through movies.

And then as I got into high school, for example, my friends, we were all theater kids, at some point we discovered John Waters, and we were just like, "What is happening?"

And so really just learning the ways that people can be in the world through movies, it really shaped how I think about the world, having come from a place that just didn't have those kinds of cultural outlets readily available to me.

- Yeah, and our generation, we didn't grow up like this generation with the cellphones and the video cameras and all these other tools that allow you to kind of capture things.

- Yeah.

- So did you, were you fortunate enough to grow up with a camera and have access to cameras and video cameras and 8-millimeter cameras and that sort of stuff?

- It's a good question.

My parents always did a lot of photography, but they never really got into video.

When I was in high school, I started to make a movie, and I will tell you that I had been involved with theater and been told that girls couldn't do the tech side of theater.

So I was allowed to paint scenery, but I was not allowed to touch the lightboard, I was not allowed to touch the soundboard.

So that, I think, really affected me in terms of technology.

So I had this VHS camera, I was taking video of my friends, but every time one of my, you know, my guy friends was around, if they wanted to take the camera, I would let them.

I recently watched that footage, and you can see how I'm developing as a cinematographer through that footage and how I'm not even, you know, I feel like I'm boasting or something here.

I'm not.

I was just really working at it as I was doing this project, and so you can compare that to the freedom that my guy friends had when they got the camera.

And so they were just like experimenting and playing, and I was really trying to figure out how to make it technically solid.

And that has stuck with me because it was this, it was because I had been told I couldn't do this thing that made me nervous about that play.

And I think about that a lot.

But I was always interested, but I also had this hesitation about the maker part of it, which is why I didn't get into the maker part of it until later in life, I think.

- Yeah, I was gonna ask you, hearing people discount you because of your gender, like, what did that do to you?

Did that inspire you, push you more, or did it make you discount yourself?

How did you look at it?

- Yeah, I think you don't notice it at the time, and then you start to realize later that you've been pushing back against it.

One of my friends always says she's too mean to quit.

[laughs] And she's not at all mean, but I love that she, you know, that that's sort of her, the way that she comes about it.

I have a very specific memory.

I lived in New York just for about a few months, and I remember being in the cab on the way into the city and seeing a billboard that said, "Welcome to the playground for the fearless."

And so that's kind of been my take on it since, like, as you get a little bit of distance and a little bit of age, it's like, "I wanna be fearless.

"I wanna, you know, this is how I wanna approach life, "and I wanna tackle these things that people have told me I shouldn't be doing."

- Yeah, give us a sense of your background in filmmaking in terms of what roles and things you found yourself, you know, kind of attracted to and the things that you, you know, kind of grew at the most.

- Sure.

So, actually, my foray into filmmaking started as an actor.

When I was a kid, I was in acting classes.

I liked being in plays, things like that.

So then when I was in college, I auditioned for a couple of commercials, sort of had, you know, background parts in those kinds of things.

My friends were making indie movies, so occasionally I would, you know, play a part in one of their films.

That was fun.

When I got to Milwaukee, I came to Milwaukee to do my PhD at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in a program called Modern Studies.

And so I was studying film and pop culture from an academic perspective.

I started working with what was then the Milwaukee International Film Festival on some of their screening committees and with a couple of their youth programs.

And through that, I was able to meet filmmakers in town, and they sort of invited me in to work in a writing capacity.

Eventually, I started producing with local filmmakers.

And so producing is really where I've done probably the most of my work here.

So several years ago, I produced a documentary called "Manlife" about the University of Lawsonomy.

I don't know if you remember the barn that said "Study Natural Law" that was on 94 down near Racine.

- Oh, I do remember that, back in... vaguely.

- Yeah, so our director, Ryan Sarnowski, he was driving back from Chicago one day, got a speeding ticket right in front of it, and was like, "I'm gonna figure out what this thing is."

[laughs] And so that took us on this whole filmmaking journey.

- Yeah.

And talk to me a little about, you're in this new role, executive director now of this incredible festival.

- Yeah.

- Pretty young, I think, for festival terms.

I mean, 2009.

That's, you know, what is that, 15, 16 years now?

- Yeah, so this is our 17th year.

So, still a teenager.

But I think we've been doing pretty impressive things for the-- you know, you're right, like, we are still young in terms of festival years.

Many festivals are celebrating, like, their 50th anniversary.

So we did get into this game fairly recently.

The fact that we have grown as much as we have and had the opportunity to showcase as many people as we have, like, I'm not sure people even know, like, we've had Willem Dafoe here, we've had Susan Sarandon here.

- And you've had Murv Seymour here.

- Exactly.

- As of today.

- Yeah, exactly.

So we'll add you to the Hall of Fame, yeah.

[both laugh] - That's amazing.

- Yeah.

- And then what kind of films are good fits for this festival?

- Truly, what we want are films that speak to audiences and that aren't getting the same kind of, like, mainstream coverage because we know, there's so much film out there right now, right?

And any time you open, like, Netflix, it's almost overwhelming.

So what we wanna do is we wanna kind of curate that for people.

We wanna tell you, like, not that we're curating Netflix, but, like, we're going to other film festivals.

What are the best films that we've seen at festivals that probably haven't played other screens in Milwaukee?

And how can we then find the local audience for that film?

We want you to come to the film and be like, "This is my favorite film I've seen this year.

And why isn't anybody else talking about it?"

Because the festival allows for these sort of undiscovered gems to really emerge.

And what I find is that when I go to festivals, truly, a lot of my favorite films do come from the festival experience, because I'm finding fresh artistic voices, because I'm hearing stories that haven't been told, you know, a billion times, or I'm seeing some cinematic technique that Hollywood's still a little bit of afraid of but I know is going to be, you know, adopted by Hollywood in, like, five years.

So you can see all of those things brewing in a festival experience.

- Yeah.

I have a little experience on the film festival circuit.

I had a project I did, came out back in, I think, 2013 or, yeah, 2013.

And hit a few different festivals around the U.S. and outside the U.S.

But what do you think it is that makes this festival unique?

And what is it offering that's unique to Wisconsin in terms of attracting, you know, projects in to screen?

- Yeah, well, honestly-- - And I only say that because I know how hard it is, you know, to get into a film festival.

In fact, I tried to get into this one, but I didn't get in.

- Oh, no!

[laughs] - But we'll save that for another time.

No, but I know, the number back then was, like, 30% or something like that.

- Okay.

- Only 30% of people that, you know, submitted a film would even, it might have even been less than that.

- Yeah, I think people don't realize how exceptionally competitive film festivals are.

I mean, truly, getting into any film festival is kind of a revelation these days because the numbers just grow and grow and grow.

I think Sundance's acceptance percentage is now, like, 0.001% or something.

It's just, it's bonkers.

But I think what's special about the Milwaukee Film Festival, a few things-- obviously, you're sitting in one of them, right?

Like, no filmmaker who comes from another city walks in here and is disappointed.

And I have screened films in, you know, the back of a coffee shop or, you know... - Murv: A bar.

- Yeah, exactly.

And so you just never know, like, what you're getting into when you agree to show at a festival and show up for a festival.

So filmmakers walk in here, and they're like, it's just, you know, it's more than they were expecting.

So we have that to offer people.

Same with the Downer.

People love showcasing their work in historic theaters.

The other thing is our audiences.

We consistently are told that our audiences, a) they show up, so we always have good crowds, but, b) we ask good questions.

So people are, you know, when they're doing the Q&As, what you want is an engaged crowd who's just, like, excited to talk about your work with you.

And Milwaukee comes out and does that.

Wisconsin comes out and does that.

And so that's really exciting that they get here and they're like, "These crowds are great.

I want to come back."

And so what we're trying to do is open up that gateway for folks to not just engage, but want to re-engage and come back with their next film and their next film and their next film.

- Is there a perfect film that's a perfect fit for this festival, you think?

- A perfect fit for this festival.

I mean, that's a really good question.

I think it's a really hard question.

[laughs] Obviously, we want things that our audiences are going to like, but that has a little bit of challenge in it, as well.

So something that, you know, something that kind of hits all the marks.

But I think to get more specific than that is going to be very, very difficult.

- Yeah, it's all subjective, right?

- Yeah, exactly.

- What do you think makes a good film?

- I like being able to see a director's vision throughout the film, so... And that perhaps makes me a little bit different than some people.

I would much rather see a director who's really trying to do something and fail a little bit than I need to see something that's, like, absolutely, perfectly put together, but that I don't think has a real point of view.

Does that make sense?

- Yeah, of course.

- Yeah.

- So, this festival runs for about a two-week period, usually in the spring.

- Yep.

End of April, early May.

- Yeah.

So you tend to get a couple hundred screenings in during that time?

- So, we have roughly 200 films, and this is features and short films.

We have really, really robust shorts programming.

People, you know, really love our, the shorts programming.

A lot of people come out year after year for, like, date night, for example.

- How many submissions you think you get for people trying to get in?

- Oh, oh, um...

I would say certainly hundreds, but I would say thousands because we're also looking at the film festivals that are screening year round.

So we have just a large, you know, large bucket of films that we're looking at.

So, and truly, when we're programming for the festival, we're also programming for the year-round programming.

So there might be something, for example, that isn't the perfect fit for the Milwaukee Film Festival, but we might pick up for our Dialogues Documentary Film Festival just because it might feel like, you know, a better programming fit with that group of films.

Or we might not have an opportunity, because of whether it's, like, distribution rights or whatever it is, that we may not play it in the film festival, but you might see it in our theater a couple months later.

So we're really looking at the year-round programming, even when we're programming for that two-week period.

- Yeah, what's life like for you when you're in this season as we're coming up to the festival and this festival's getting ready to launch and you're getting ready to be into this, you know, kind of crazy period when it's nonstop?

What's it like for you?

- Busy.

[laughs] Yeah, it's a lot of, for me right now, it's a lot of, you know, just, like, talking to people, getting people interested in working together.

We want to really build community connections.

So whether it's, like, working with another nonprofit or a specific organization, a corporation who really wants to have a film that sort of speaks to their mission or somehow speaks to what kind of company culture they're trying to build.

So really trying to make those connections.

I'm also watching films on the side.

I fully understand that people wanna talk to me about the movies, too.

So we have this big team, and right now, I'm trying to do a little bit of everything, or moving into festival season, I guess.

I am a woman of many hats, as they say.

- You probably have to be, right?

- Yeah, yeah.

- So, what do you see, now that you're in this new role, what do you see as the big thing that you're trying to bring to this festival that maybe hasn't been part of it before and taking it to the next level?

- Yeah.

Well, one of the things that we're doing this year is, we have, we're turning our two festival theaters, the Oriental and the Downer Theatre, into more of a condensed festival campus.

And I'm talking about this because it sort of sounds like downsizing, and that's not how I'm thinking about it at all.

When I go to a film festival, what I know is that I want to feel like I'm at the festival when I'm outside of the theater, as well.

So when I'm in the restaurant across the street, when I'm in the bar down the street, when I'm at the bookstore.

Everything feels activated by the festival.

So I think that's something that we're kind of going back to our roots to do, so that we can make sure that it's not just us showing a lot of different kinds of movies for two weeks, but that all of the neighborhood businesses are part of it.

So that's something that we're, again, activating this year that we've kind of moved away from in the past few years.

- I wonder if you could say, tell us, why do you think filmmaking is important?

Why is storytelling important?

Why is having this kind of an event important?

Especially to people of Wisconsin and people that love film.

- Yeah.

Again, this goes back to my roots, I think.

I had so much empathy for the characters that I was seeing on screen who were living experience that were totally removed from my own.

I think that's a really key part of the film-going experience, so that we can understand the stories or social issues or whatever it is from outside of our own experience.

And there is something about the cinematic experience that specifically allows for that because of the visuals and being able to sort of get into the shoes of a character and live their journey with them, even if it's just for an hour and a half.

I think that's crucial.

The other thing I think is as crucial as ever about cinema-going right now is community experience.

So when you go to a movie, if you go to a, you know, a comedy with a bunch of other people and everybody's laughing, you've just had a great time with 100 or 300 or, in the case of our main house, a thousand other people, and you've all just experienced that joy together.

I think coming out of the pandemic, people have maybe forgotten the importance of some of those kinds of experiences and how they bring communities together and how they make us sort of remember that we are in a shared human experience and laughing together, crying together, you know, just having that.

And the fact that we can offer that on a weekly basis, I think, is, you know, astounding.

- Yeah.

I'd love to get your thoughts on technology and how that's impacting filmmaking because we know that there are people out there that can make a movie with an iPhone.

They're using their iPhones as cinematic tools.

And we all have, you know, editing systems, not just on our laptops and tablets, but they're on our phones now.

- Yeah, exactly.

- Good for filmmaking, bad for filmmaking?

What has it done to filmmaking?

- Honestly, I'm here for it.

And, you know, I love a good TikTok as much as the next person.

I feel like that's a totally different kind of filmmaking than what we're going to see in, like, a Martin Scorsese film.

So I think that range is great because sometimes you do wanna just sit down and engage with something for 30 seconds.

And the way that people are so creative with the format of a phone is, again, it's just a very, very different experience than the way that people can tell a story over the course of, you know, whether it's, like, two hours or two-and-a-half hours.

Or even thinking about somebody like David Lynch.

A lot of people talk about the second season-- or, not the second season, the "Twin Peaks: The Return" as like a, you know, whatever, 8, 10-hour movie instead of, like, a television show.

So it's really about what the creators are bringing to the tools that they're using.

I don't think the tools necessarily dictate whether or not something is good or bad.

I want storytellers to find the right tools for them.

I love that so many people are going back to shooting on film now because I think that there's a way in which when you're shooting, you know, whether it's 35-millimeter or, like, Super 16, you have to be a little bit more deliberate with how you're setting things up and what you're capturing and how all the pieces are fitting together.

And there's a richness to that visual look for me that I love.

So I think, you know, we have the phones, we have just amazing digital cameras, but we also have these tried and true, you know, like, 35-millimeter cameras.

And a lot of people are shooting on IMAX now-- amazing.

So the fact that filmmakers get to find the right tool for their story, I think, is remarkable.

- Yeah.

And what's your message to someone out there that has a story they want to tell, have a project they'd like to get done?

What do they do, where do they start, and how do they make it happen?

- Yeah.

My advice is always just make it.

[laughs] Try not to overthink it.

- Wait, that's all you have to do?

- Yeah.

- Just do it?

- Just make it.

So, if you want to write a script, just write the first draft because the only good first draft is a finished first draft.

And then the writing comes in when you're revising that first draft.

So I think people are very worried about getting a good first draft out.

Just get it out.

Like, just, you know, really get that thing out, and then you can start crafting it.

You can get feedback, you can start working on it.

I try to encourage makers not to be too precious with their work.

Take it seriously, certainly, but I think every time we make a project, we grow.

And so if you're so worried about getting everything just meticulously right the first time out, you know, we're always going to make mistakes.

I want to say it was Claire Denis who said something like, "It's only after the movie's finished that we pretend all the mistakes were fixed," or something to that effect, right?

And just following your creative vision through the script and making sure that you're really sticking with that through the filmmaking process, because you want to be proud of the thing that you make.

If you feel like you're compromising too much, then, you know, it may or may not work out in the end.

This sounds very weird, but my partner likes to say it's just as hard to make a bad movie as it is to make a good one, and that's kind of true.

So as long as you're following your own artistic sort of passion and making sure your voice is in there, I feel like you've succeeded.

- Yeah.

And you're sitting amongst a few aspiring filmmakers.

And we always talk about the concept of, you know, is less more?

What's your advice in terms of, you know, should young filmmakers, you know, take on a big project, you know, feature length, or is it better to take on something a little smaller and smaller chunks and-- any thoughts on that?

- I think it depends on the story, right?

Because I think there are stories that want to be told in a 5 or 10-minute period.

There are other stories that want to be told in a 90-minute period.

And I do think it's a skill to figuring out which one is the right fit.

In many ways, I think it's harder to make a good short film than it is to make a feature film.

Short films just have a specific cadence.

And I've seen a lot of people try to fit a feature into 15 minutes, and that's, I mean, it's just a hard task, and it often doesn't work because it's just not the same format.

So I think, again, just thinking about what is the story that you want to tell, why do you want to tell it, and then what is this story telling me that I should be doing with it?

Sometimes you start with a feature, and it's a better short.

Sometimes you start with a short, and you're like, "This really needs to be a feature."

So also maybe having that flexibility to let the film dictate to you as you're moving through it.

- Yeah.

I'd love to hear your thoughts in terms of Wisconsin as a filmmaking destination point.

How is the state doing?

You know, we talked to John Ridley about some of this.

And, you know, having lived in Louisiana, I was there during the big boom.

- Mm-hmm.

- When studios started to leave L.A. to do things there, in the Carolinas, especially New Orleans.

And now we know Atlanta is kind of the second Hollywood.

- Yeah.

- What can we do here and how are we doing here to attract those kinds of opportunities here for filmmaking?

- Yeah, well, I'm not sure if John Ridley talked much about Action Wisconsin, but that's-- - I don't think he did.

- Okay.

It's an advocacy group, and they're working tirelessly for us to get some tax incentives built into-- And in fact, the governor's budget was just announced, and these things are built in.

So right now, there's a big push to try to get more tax incentives for makers in the state of Wisconsin.

We have kind of a tremendous local filmmaking community or, you know, statewide, different pockets of people who are doing amazing work and are very, very, very supportive of one another.

But we really do need this influx of work from the outside to kind of boost everything.

So Action Wisconsin is working to try to bring some of those issues to legislators so that we can build some of this in in a way that systematically works for the state and then attracts some of this outside production.

So "Top Chef" was, you know, the last season of "Top Chef" was filmed in Wisconsin, brought just a bunch of, like, economic tourism to different parts of the state because people were seeing this restaurant or that restaurant and then just wanted to go there and try it.

All of that is possible as a reverberation from filmmaking, television-making.

So it's not just the filmmakers who would benefit from something like that.

It's really the whole state that benefits from that kind of initiative.

- Yeah, I was gonna say, do you feel like there's anything specifically unique to Wisconsin... - Absolutely.

- ...that we could really market and draw people in?

- Yeah, I mean, the fact that we have, you know, the north area of Wisconsin, how gorgeous that is, the hills, the trees, all of that.

The Driftless region, gorgeous, and Lake Michigan.

So we have all of these different terrains.

We have cities like Madison and Milwaukee.

They're, you know, they both pass as a city.

They also both have their own flavor.

That's really attractive.

We have so many great small towns.

Everybody wants that.

I know that, like, you know, the Hallmarks and the Lifetimes are dying for the kinds of small towns that Wisconsin has to offer.

So we have so many different possibilities.

We have a lot of great architecture that has never been on film.

I don't know if you've noticed, but there are, like, a couple of diners that seem to show up in, like, every Hollywood movie.

And so there are people in Hollywood that are looking for a state like Wisconsin.

So it's like, "We need, you know, we need an old diner.

"We don't wanna use the same old diner "that everybody's seen a thousand times.

"You know, can we go to this place "and use it and have the perfect location for what we need for our movie?"

- I wonder, when you look at films, do you see the same things I see sometimes?

I sometimes can look at a movie and I can-- "That's Toledo."

- Yep.

- Murv: "That's Shreveport."

- Yeah.

- Murv: "That's New Orleans."

So do you see that, too?

- Oh, absolutely, yeah, yeah.

And once you start to pick up those markers, it takes you out of the film experience.

- Yeah, that's true.

- Yeah.

- I'd love to get your thoughts on diversity in filmmaking.

How are we doing, and how is this festival doing?

And is that a big part of your mission in terms of, you know, what you bring to the table as far as, you know, expanding things in filmmaking?

- Yeah, absolutely.

I will say, industry-wide, we're not doing as well as I had hoped we would be doing.

There was obviously a big push, maybe, you know, I guess it was just before the pandemic.

And this tends to happen in Hollywood, where there is a big push and then things start to even out.

And then as there's not as much focus on it, then things sort of don't even out in the same way.

I think Hollywood's in that kind of period right now, so I'm definitely keeping an eye on that.

One of the big opportunities, I think, with a festival like the Milwaukee Film Festival and the year-round programming at the Oriental and the Downer is that we can kind of help elevate some of the films that aren't getting the big push from Hollywood dollars.

So we definitely want to just make sure that we're reaching, like, all kinds of stories and storytellers, and making sure that we have enough programming there that we don't feel like we're sort of putting things in, like, one category.

I feel like this is complicated to explain, but we're really trying to make sure that we have diverse programming throughout the year so it doesn't feel like, "Oh, okay, "well, now they're doing this kind of thing or now they're doing this kind of thing."

Because we know that our audiences are diverse.

We know that our audiences want all kinds of stories.

And so we don't want to pigeonhole the stories that we're showcasing because that, you know, it just doesn't benefit any of us.

- Yeah, with the current climate, with all the attention on DEI and funding being pulled in certain areas, does that scare you at all?

Does that keep you from moving forward on some of these things?

- I'm gonna say no, and I say no in a very sort of tenuous way just because, as you know, every day, things are happening in the news right now.

And so it's hard to predict, like, what's coming.

But Milwaukee Film is incredibly committed to its diversity, equity, and inclusion programming and to the different initiatives that we're doing, the different kinds of community groups that we're working with.

I'm not somebody to back down from a fight.

So, you know, if something happens that, if something happens that we get called out for, I'm willing to go to bat for it because I think it's incredibly important.

It's just, it's-- I wanna be future-looking, and, yeah, we're the future.

[laughs] - And what do you think you bring to the table as a female film filmmaker that a male wouldn't bring?

How does that change the perspective of the story, I guess?

- That's a really good question.

I'm, hmm.

I'm not sure, truthfully.

I feel like because I've been sort of in the mix with filmmaking and sort of the film canon for so long, I feel like I have been having some of the discussions that are happening with gender in film, that I've been having these conversations for decades, so it doesn't feel different to me right now.

It feels just very much part of who I am.

So I'm not sure that I'm doing-- I think it's really hard for me because it doesn't feel like something that's new to my discovery about myself and my approach.

- Yeah, I was thinking, I wonder if, you know, when I watch a movie or a story, I don't think about the gender or sexuality or race of that particular filmmaker.

I mean, do you think of storytelling and filmmaking in the same way, I guess?

Or is that, like, you're, it sounds like you haven't really thought about it, so it's just not something that you think about, right?

You just do.

- Yeah, I think it's tricky because there are certain stories that I feel like it's important for certain creators to be able to tell.

I also don't want to pigeonhole anybody.

So I feel like, you know, I'm not-- uh, sorry.

- It's okay.

- [laughs] I'm not allowed... - You're allowed to touch yourself.

- I just don't want to affect the mic.

- Oh, I just did the same thing.

Sorry about that, guys.

Sorry about that.

- I don't want to pigeonhole anyone.

And what I mean by that is that, you know, I'm personally not going to make a film about, like, the queer Black experience because that is something that I would feel very much a fraud entering into.

However, if I were a Black queer filmmaker, I would also not want to be told, "The only stories that you can tell are from this perspective."

I might want to tell every story from that perspective, but I wouldn't want to be told that that's, you know, the only thing that I could do.

So that's my hesitation with these kinds of questions, is that I want lots of people to have expansive opportunities.

And so I'm afraid that if we start to, you know, too much direct people in one way, that what that ends up limiting are the opportunities for all of these people who are being directed in one way.

Truthfully, the winner in that situation is probably the people who are already in Hollywood and already well-connected who aren't thinking like that.

And so, so I want to be able to figure out how we can support all of these voices without, again, limiting what people are told they can or can't approach or say or work on.

- Yeah.

What's the hardest part about being a filmmaker, you think?

A young filmmaker, an unknown filmmaker, or a coming-up filmmaker.

- Yeah-- money.

I mean, that's, truthfully, that's the boring answer.

But all of this stuff costs money.

When you're young and you have friends who are willing to, like, show up on the weekends, you can get away with doing things for less money.

As soon as everybody has, like, different financial obligations or family or, you know, we just get older and get more tired, then those kinds of things get more difficult without the funding, so, so that's always a consideration.

I do think the other thing that is difficult is that filmmaking is such a collaborative medium that you have to trust your own vision and you have to trust the vision of many other people as well.

And there's a real balance in that.

So you're sort of always project managing, but you're also trying to do this singular thing.

That's where, if you're a director working with a producer that you really trust, those things can go much more seamlessly.

I often encourage young directors to work with writers because if you're working with a really great writer, they solve a lot of problems for you that you don't even know that you're necessarily having because you're so tied to your own artistic vision.

So I think finding really, really great collaborators that you can trust and grow with is also a way to balance out that money issue.

- And what's the biggest joy you get, Susan, out of this kind of work?

- I love it all.

[laughs] I mean, I'm a dreamer, so I get excited about the ideas.

If you are a producer and you're not excited about the idea, like, you're sunk.

So I'm very lucky that I can get on board with just this little nugget of a thing very early.

I love seeing all the pieces come together.

I think it's exciting at every moment.

I love when you have a first cut because when you have a first cut, you're like, "All right, we've got a movie."

And that feeling sets in in a different way.

And then you sort of, you know, work through the labor of getting that to where you're finally in a cinema and then watching it with an audience for the first time.

It's, yeah, there's nothing like it.

So I'm just in for all of it, I think.

[laughs] - Yeah.

What's the hardest part about what you do?

- The hardest part of filmmaking?

- Murv: The hardest part about, well, we'll take that question, too.

- Oh, the hardest part about filmmaking.

- Well, you kind of said that, you said money.

- I did, yeah.

- I was actually asking, what's the hardest part about what you do, your work and your role, in terms of, leadership and cultivating films, and things like that?

- Yeah, well, it's no surprise to anyone that I have a hard time saying no.

[laughs] - I mean, y'all said no to my film when I tried to get in this festival back in 19-- 2013.

I'm not trying to bring up old wounds, but, uh, but that wasn't on your watch.

- Yeah.

[both laugh] We'll figure out how to remedy that.

We'll figure it out, we'll work on it.

No, I get so excited about things that I have to kind of narrow myself, and make sure that I'm working in scope.

My partner and I have an agreement where sometimes I ask him, "Should I do this thing?"

And if he tells me, "You should not do that thing," then I have to believe him, just because I do tend to really, I really wanna help people.

I really wanna build community.

And so I get, yeah, I just get on board with things easily, so.

That's the thing I need to reel back in.

- Every now and then, we do this thing in this segment where we give out superpowers.

You get to do whatever you want to do.

Nobody's gonna stop you.

It's gonna happen, get it done.

- Yeah.

- What's your superpower, Susan?

- Oh, what's my superpower?

- Murv: Yeah.

- Honestly-- so, I recently learned the term "super connector."

I think that's my superpower.

Because if you told me, like, "Oh, I'm looking to meet people who do X, Y, and Z thing," I'm immediately-- and this is just instinct-- "I know people who do X-Y-Z thing, and so I'm gonna try to connect them to you."

So I think that that's the superpower I bring with me.

And I think that's a skill that I'm excited that already feels very natural to me.

- So collaboration, basically?

- Yeah, collaboration.

And just expanding people's networks.

Like, I want everybody to know everybody because you never know when that person that you met in line for the movie is gonna be the person who's making puppets for you on your next production.

You know, all of those things are possible.

So just making sure people know each other and don't feel the fear of reaching out.

- How do you think somebody knows that filmmaking is for them, and storytelling is for them?

Any idea?

- Oh, that's a really good question.

I think you kind of just know if you-- there are people who want to connect with the world in different ways.

Some people are always storytellers.

Like, from the time they're a child, they're just, like, you know, gabbing in your ear and wanting to tell you a story.

And those folks might find it because of their experiences.

That's probably how I found it.

I know people who find it because they find a filmmaker who, somebody like David Lynch, who expands their world so much that they're like, "I never knew movies could do this."

And so that's their entrée into it because maybe they're coming from more of an artistic background or something than I was.

And they're like, "This movie is speaking to people on a level I hadn't seen before."

And so that gets them excited about engaging artistically with the world in that kind of direction.

I think moving into it, again, I want everybody to try to make the movie that they want to make.

I think what gets difficult is then figuring out how to sustain your career.

And a lot of that is, you know, whether or not you feel like you have to.

Because it's hard.

Moviemaking is hard.

And so there are a lot of people who make one film, and they just don't have it in them to do it again.

And there are other people who do one, and they're like, "All right, that one's done.

Gotta get on to my next one," and they're just go, go, go.

So I think that's where you really find out, you know, what's in your blood in that way.

- What's hot right now in filmmaking in terms of genres and that sort of thing?

- I mean, horror is incredibly hot.

Genre audiences come out for their genre.

So that's fun.

There's a lot of really interesting horror happening right now.

Also queer cinema is, you know, queer audiences are really eager for the stories that are being told and the fact that there's many more of them.

I think that that's a very loyal audience, too.

So that's exciting.

I think we're at a moment in Hollywood where Hollywood's really trying to figure out what to do.

We're seeing the superhero movies kind of, you know, they're just on more unstable ground than they have been for a long time.

So I'm excited because when Hollywood is trying to figure out what to do, historically, that means that really great movies start to come out of Hollywood.

So I'm very hopeful for the next few years of Hollywood.

I think they're going to find some ways to be a little bit more experimental and take some risks that, because they're trying to figure out what pays off for them right now.

So I think it's an exciting time.

- What does it say about me when I look at horror and they scare me?

It literally scares me.

And my heart jumps out of my chest.

- Yeah.

- I don't like that feeling when I'm watching a movie.

- Yeah.

- You know, because I don't know what's gonna happen.

- Yeah.

- Like, it literally scares me.

I enjoy spy movies, I enjoy action movies, I enjoy comedies.

- Yeah.

- But horrors, like, the gore and-- and they do it so well, like, the whole "Saw" series.

- Yeah.

- I had to go see that by accident because I was going to see-- I'm trying to think of what was out at the time.

I can't remember the other movie that was out, but it was already sold out.

- Oh.

- And that was the only movie that was showing around that time.

So me and my friends, we went to that.

- Yeah.

- And I had a really tough time watching that movie.

- Yeah.

I mean, as you would, right?

I think you're supposed to have-- I hope people have a tough time watching that movie.

- But I always say, like, when it makes me feel something, whether it's the fear or the fright or the joy or the pain or whatever it is, I feel like that movie's been effective.

- Yeah, and I think there are different kinds of horror.

You know, "Saw" to me is not my, like-- I agree.

Like, I'm not one who's like, "Oh..." - Murv: There's like, five or six of those movies.

- It is true, it is true, yeah.

And some people love that.

And they're there for the gore and, like, they're all in.

[laughs] I think I'm-- maybe "The Substance" is a good example of, like, lots and lots of gore.

It definitely, you know, goes all-out.

I don't know if you've seen it, but it is not for the, you know, for people who don't like blood.

- Which movies?

- "The Substance."

The Demi Moore film.

But it's really all about a reflection of her body and control and aging.

And so there's this interesting sort of discussion happening around, you know, the body element of it that then takes a very gross turn.

- Yeah.

- Yeah.

- I may have to wait on that one.

[Susan laughs] Future of filmmaking.

Where are we headed?

What do you think, what do you see?

What's out there that's not being done that needs to be more of?

- Hm, oh, wow.

Um, I think investing in, like you were talking about earlier.

I think we still need to make sure that Hollywood is investing in diverse directors, diverse storytellers, diverse creatives.

We have not begun to touch, I don't think, sort of the depth of the Black experience in America or the Latinx experience in America.

There's so much more to be... - You know, the interesting thing about that is that those films, some of them are out there, but they're not always from the African-American, Latino experience.

- Yeah.

- You know, it's like, I remember seeing, what's the, is it "Flowers of the..." something.

What was the one with, just came out last year, big film that... - Oh, "Killers of the Flower Moon."

- Yeah, I saw that, and if I were telling that story, I think I would have gone a different direction.

- Mm-hmm.

- But I understand that, you know, as a filmmaker, you know, each filmmaker has their perspective in terms of what part of that story they're drawn to.

- Yeah.

- You know, because I think I was looking to learn more about these people, you know, who had this horrible thing happen to them.

And that story was more focused on, you know, people that came in to exploit those people.

- Yeah.

- You know?

And so that's one of those examples where I could see, you know, if someone else did that story, they might see a totally different story.

- Yeah, I absolutely agree.

And I think that movie is a great example of this because, again, Martin Scorsese, he directed it.

Like, he approached that story... - And he's, like, the best in the business basically.

- He's amazing.

And that movie is really a gangster movie, right?

Which takes him back to kind of his roots about, like, you know, the, like, gangster culture.

You can see all of that playing out in that film.

But you're absolutely right.

That's a very different kind of approach than a lot of directors would take to that material.

So I think this is exactly why, yeah, that we want to make sure there are different people in the room or having these opportunities to make films with the kinds of, you know, they might not get a Scorsese budget, but at least with a really respectable budget, so that they can follow their vision and really dive into what they have to say about that kind of moment in history.

- Yeah.

Well, man, we have talked about a lot.

I don't even know if I'm gonna sleep well tonight after talking about some of that horror stuff.

[Susan laughs] But I know you have to be excited about the future for this particular festival.

- I really am.

- After 17 years now.

- Yeah.

- Um... - Yeah, I can't wait.

- In 100, what will it look like in 100?

- What will it look like in 100 years?

Well, I will not be here, sadly.

- Are you sure?

[Susan laughs] - I hope, I mean, here's what I know.

This theater will be here in 100 years, and I'm not sure the shape of what will be happening inside of it will look like.

I think there's, so, there are so many opportunities for the ways entertainment can grow as the future moves forward, but what I think will be happening is that people will be continuing to come to a space like this to congregate, to celebrate art with one another.

So that's my goal for 100 years out for Milwaukee film.

- Yeah.

Susan Kerns, thanks for stopping by.

- Yeah, thank you so much.

Thanks so much for having me.

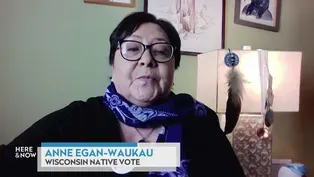

Wisconsin Native Vote Highlights Use of Tribal ID for Voting

Video has Closed Captions

Wisconsin Native Vote notes how tribal ID is a valid type of voter identification. (3m 36s)

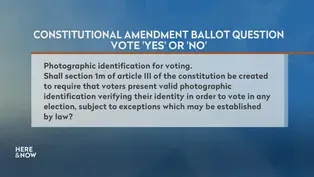

Wisconsin to Decide on Voter ID Amendment in 2025 Election

Video has Closed Captions

A state constitutional amendment on voter ID will be in Wisconsin's spring 2025 election. (1m 8s)

Why a Racine Referendum Reflects Wisconsin School Money Woes

Video has Closed Captions

Racine faces a critical moment for school funding with a $190 million budget referendum. (7m 3s)

Why Wisconsin's 2025 Schools Superintendent Election Matters

Video has Closed Captions

The race between Jill Underly and Brittany Kinser centers on testing and school funding. (6m 27s)

Who Has Momentum for the 2025 Wisconsin Supreme Court Vote?

Video has Closed Captions

The 2024 presidential vote set the stage for the 2025 Wisconsin Supreme Court election. (6m 39s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipHere and Now is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin